This article reports on a study using systemic functional linguistics (SFL) as a metalanguage in primary grades to help students develop a deeper understanding of characterization as well as to promote dialogic interaction within the classroom. The researchers used Martin and White’s appraisal analysis, specifically positive/negative evaluation and turned up/turned down (graduation), and the process types, “the ‘happenings’ in a text” (sensing, doing, being, saying) to help understand direct and indirect characterization, how characters “show” and “tell” their emotions and motivations (Moore and Schleppegrell 97).

Using a Metalanguage in the Classroom

When reading and discussing literature, teachers and students have a literary metalanguage (terms such as symbol, metaphor and characterization) to help make meaning of stories and discuss author’s craft. When responding to writing, teachers often use the metalanguage of traditional grammar in service of improving the “correctness” or “mechanics” of student writing. (Moore and Schleppegrell 93)

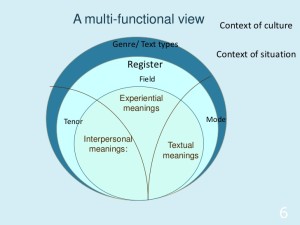

In education we most often use literary and traditional grammar metalanguages, but rarely do we employ a functional metalanguage, such as SFL, “that connects language forms to meanings in contexts of use” (Moore and Schleppegrell 93). A literary metalanguage can provide a close reading of a text, often devoid of context, while a traditional grammar metalanguage can only focus on correctness, whether a students’ writing is “right” or “wrong.” What I find so interesting about Schleppegrell’s view of the functional metalanguage is that it provides a way of uniquely interfacing with the content of a text, providing new avenues and areas of analysis. I am also interested in the ways in which classroom discussion and dialog can be fostered once students have a working knowledge of the SFL metalanguage.

Besides giving teachers and students a common language for discussing and analyzing texts, which goes beyond literary metaphors and traditional grammar, the metalanguage can also be used by researchers to analyze students’ texts. Here, student writing becomes important data for researchers. As I am researching how students use the SFL metalanguage in relation to visual analysis, I can use the SFL metalanguage to analyze their writing.

What does the SFL metalanguage have to do with multimodal visual analysis?

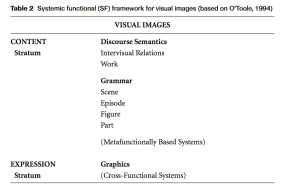

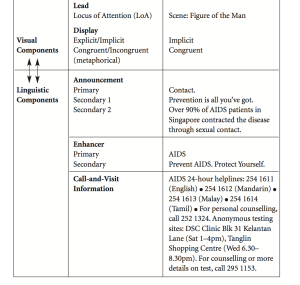

So, what is the connection between students in primary school learning SFL to better understand characterization and multimodal visual analysis? Both textual analysis and visual analysis use SFL as a metalanguage. For instance, the functional labels above – participant, process, polarity, etc. are used in visual analysis as well (see Table 1). My view is that students can first learn the SFL metalanguage through doing something “fun,” like analyzing commercials and websites, and then learn how the metalanguage can be applied to texts, “drawing on the SFL notion of movement back and forth along a mode continuum” (Moore and Schleppegrell 94). SFL allows for this shifting of modes, from visual to textual analysis and even to discourse analysis.

Integrating Textual and Visual Analysis in the Classroom

I have not yet been able to fully integrate visual and textual analysis as a mode continuum in the classroom, instead mainly focusing on visual analysis, although I have made it clear to students that the metalanguage they are using for visual analysis comes from functional grammar. Textual analysis can be integrated more easily in primary and secondary school settings, where teachers have more time with students, not to say that integrating SFL textual analysis is impossible. In the future, I would like to develop worksheets and create activities, which use SFL to interact with content meaning. Although most of this research has been done in primary grades, it would certainly be useful on the college level. If there was a greater push for SFL nationally, especially to prepare students for the rigorous standards of Common Core, students would become familiar with SFL at a young age, creating positive literacy development for the future.

Works Cited

Moore, Jason, and Mary Schleppegrell. “Using a Functional Linguistics Metalanguage to Support Academic Language Development in the English Language Arts.” Linguistics and Education 26 (2014): 92-105. Web.